Northern Somalia is steeped in a complex history of colonialism and clan conflicts that date back several centuries. British colonization in 1884 resulted in agreements with the native clans, such as the Isak, with the aim of securing their interests and protection. However, not all tribes were party to such agreements, hence the historical animosities and conflicts that continue to date.

It was in response to these hostilities and the harsh legacy of British colonial control that the SSC Khaatumo area was established. They have never entered into protection agreements with other tribes, which has led to continuing strife concerning territory and power struggles in the region. For the last 22 years, the people of SSC-Khatumo have been incredibly persistent in defending their rights to territory and heritage. It is a complicated history that must be recognized if the dialogue among clans and partners is to be fostered in light of territorial disputes and resource management for reconciliation and healing.

During colonial times, northern Somalia did not have a spirit of community, and the isolation of tribes within their respective territories hindered the development of any solid ideology or approach that could be summed up as “We Are Northern.” After independence, several groups were formed with the aim of fostering unity, including the USP, which brought together delegates from various regions in a bid to get them to inspire national unity. This integration process faced opposition from historical clan disputes, territorial disputes, and even the pressure of the colonial rule that was still there.

The claim to Somaliland’s statehood, as has been advocated, is based on its colonial history, where the supporters try to make it akin to the experience of its British colonial counterparts. However, the idea of the politics of Somalia being divided between south and north is a fallacy. A diversified past and the clan-based setup of the people of Somalia have prevented the emergence of a single nationality. Scholars argue that either a devolved unitary system or an equitable federal system comprising of 18 regions should be formed, which shall provide regional self-governance with national unity.

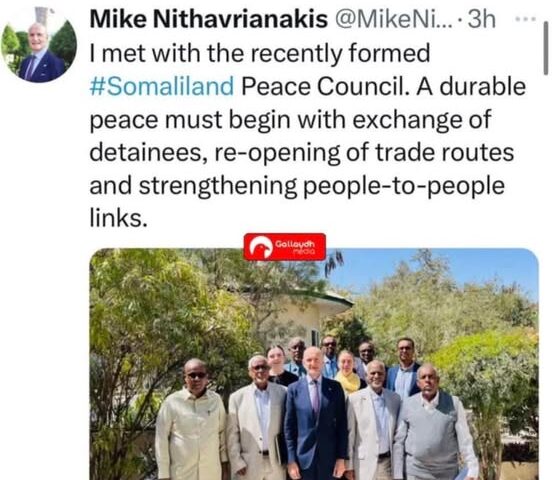

That is why the leadership is required to build relationships with locals, take into consideration their wishes and rely upon the clans’ decisions, and use the principles of participation. Otherwise, in the future, northern Somalia can only take a step toward peace and cooperation in the region.

The southern part of Somalia, shaped by Italian occupation, is divided into five federal governments and could be a template for the north. In the north, three regional federal governments can be easily implemented; however, deep thought must be taken to prevent the north from being controlled by one tribe only, which may lead to a probable desire for independence.

Effective governance means that local populations are involved and clan sensibilities understood; policies are inclusive. The model will strike a balance between regional self-governance and national unification in ways that meet the peculiar needs of each tribe yet add to the joint growth. This requires politicians to place the interests of inclusive government above personal ones and to integrate cooperation between tribes and regions.